The past couple of weeks have been fruitful at Field & Pantry. A lovely crop of new subscribers have found their way to this space—welcome!—while I’ve been working on crystallizing my mission and refining my About page. Why am I here? I’ve been asking myself. (Not here on the planet, which is another thing I sometimes wonder when my eyes pop open at 4 am, but here on Substack, which is also worth asking, even if it’s a touch less existential).

This is what I came up with:

I was raised in a house where cooking was as natural as breathing, but for the longest time, I worked as an editor at parenting and women’s magazines, and kept food as a side passion. It was only when I approached a certain significant birthday that I heeded a now-or-never feeling in my bones, quit my job and enrolled in full-time chef school. Two gruelling, gratifying years later, I returned to journalism as a chef, ready to dig deep and explore my relationship with food on the page.

This newsletter is the first part of that coming home—a happy plunge into food stories and recipes that will, I hope, help you connect with a sense of joy and abundance in the kitchen. The second part is my upcoming food memoir, How to Share an Egg: A True Story of Hunger, Love and Plenty, to be published by Ballantine Random House (US) and Appetite Random House (Canada) in January, 2025.

As my book progresses at the necessarily glacial pace of traditional publishing, it has been fun and gratifying to publish here, directly to you, whenever I can.

Lately, it’s the growing season I’ve had on my mind. Seasonality is one of my pillars—that’s what “field” refers to, after all—and although it’s currently a sub-zero March day in Toronto, it’s still the beginning of spring. Soon there will be ramps and fiddleheads, asparagus and one of my greatest loves, rhubarb, which will have my next post all to itself.

In the meantime, maybe because there’s still snow on the ground, I’m thinking not of fields and farms, but of my childhood in northwestern Canada and Mr. Rankin, our fruit man. I watched for his dented red van on Tuesdays, I think. I’m not young but I’m not that old either, and it was anachronistic, even in my childhood some decades ago, for fruits and vegetables to be delivered by a guy with a truck instead of simply purchased at the grocery store. It must have been my Baba Sarah, Mr. Rankin’s customer a generation earlier, who arranged for her excellent fruit man to come to her daughter’s brick and wood house on Valleyview Crescent.

He was ruddy-cheeked, in dark green coveralls—or maybe they were Carhartts, not that I would have known such a thing at six or seven or eight. What I did know was that the back of his van was an enchanted place of the sweet and juicy and vegetal and earthy. I was born longing to go to a farm; to milk cows, pick strawberries and gather eggs, but we were city people and we were tethered to our restaurants. My father wore suits and polished his shoes before going to work. Mr. Rankin had dirt under his nails.

The red van went on and on, a field on wheels, with plants growing out of shelves and crates and baskets. I walked the narrow aisle, sampling whatever I wanted—cucumbers the size of my pinkie, tender peas in the pod, cherries from the Okanagan. My sisters and I hung the doubles from our ears like earrings, and if there were three together, it was a lucky day, indeed. Sometimes, if Mr. Rankin came when my mother wasn’t home, he’d send one of my sisters into the house. “Tell me what’s in the fridge,” he’d say, and when she came back, he’d make up the order using his judgment. He wrote prices on the brown paper bags with a pencil he took from behind his ear.

In Alberta, the growing season started late. It was April or even May by the time we swapped our down jackets for t-shirts, by the time the house took on that specific spring smell. It couldn’t have been more than a few weeks a year that Mr. Rankin was part of my life, and yet, I remember him so clearly. We had a milkman, too; our house had a little cubby at the back door, where Mom would leave the order and in the morning, there would be milk in glass bottles, and cottage cheese, and maybe some orange juice.

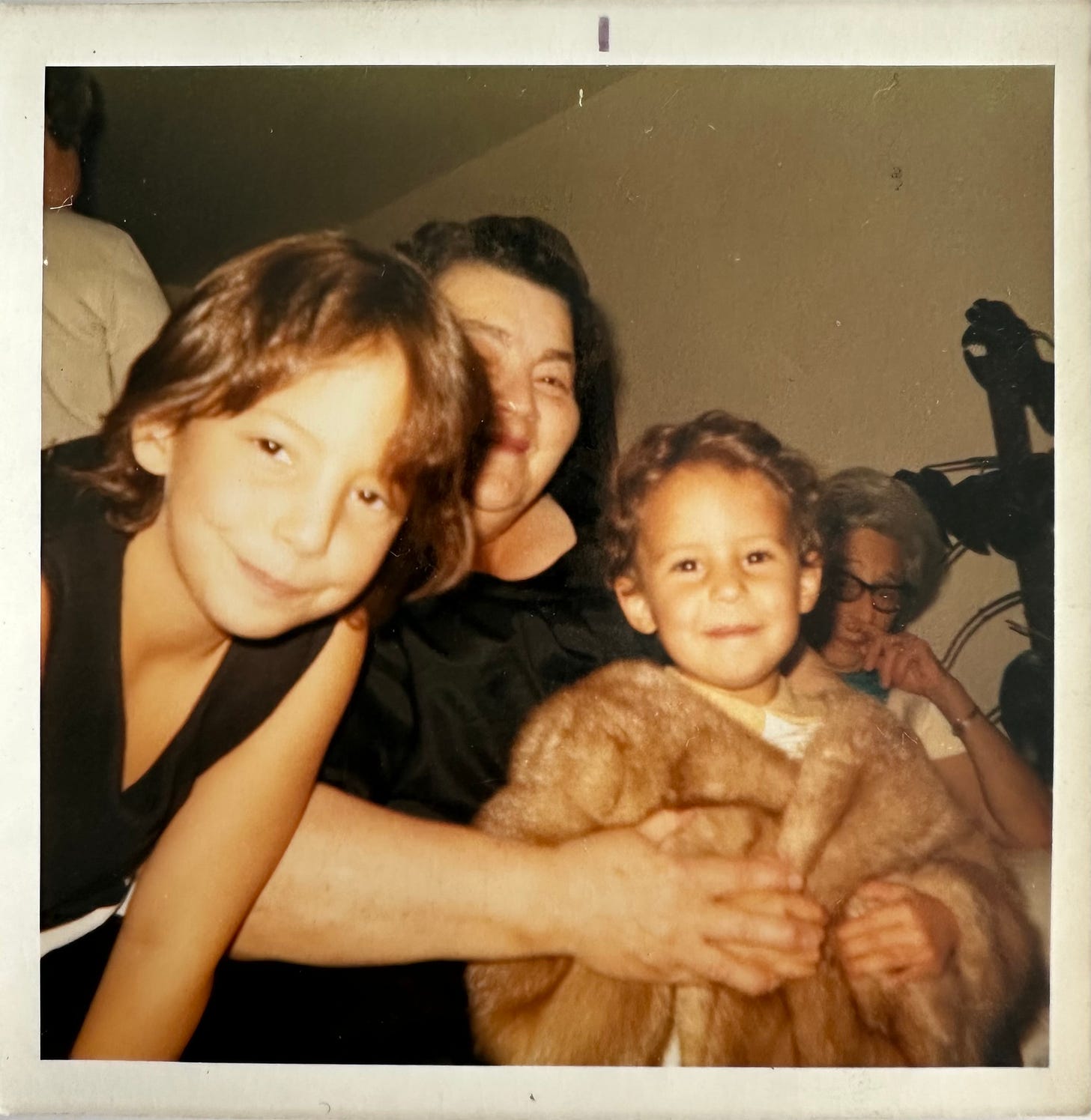

Nostalgia is a funny thing—it seems like these routines were already disappearing while I was living them, that I knew they were the end of an era, and not even my own era but the one before mine. The truth, I’m sure, it that I didn’t think these things special at all. But now… Now I can’t stop the pictures from floating into my head. Mom in her flowered pants, silk scarves tied in her hair; Dad with his long sideburns, fun, busy, always planning a new restaurant, always changing and reinventing. I think of Baba’s wide body and strong arms, beating egg whites or wrapping me in someone’s fur stole. And of Mr. Rankin, hopping out of his red van, planting early seeds of meaning in my young mind, even while doing nothing more than going about his ordinary day.

Even though we grew up on different sides of the world and different time periods, this post reminds me so deeply of childhood. I grew up in a small-working class area just outside Belfast in Northern Ireland. There were a few farms around about. We had a potato woman called Roberta who came door to door every other week, selling bags of spuds. Sometimes my granny would have money sitting on her telephone table near the front door and I would ask her if I could have it to go up to the shop to buys sweets. "No, it's for the potato woman," she'd say. No one called Roberta by her name - she was always just the 'potato woman.' Reminds me of your fruit man. ❤️ Also - for whatever your reasons are for being on Substack - I'm glad you're here, Bonnie xx